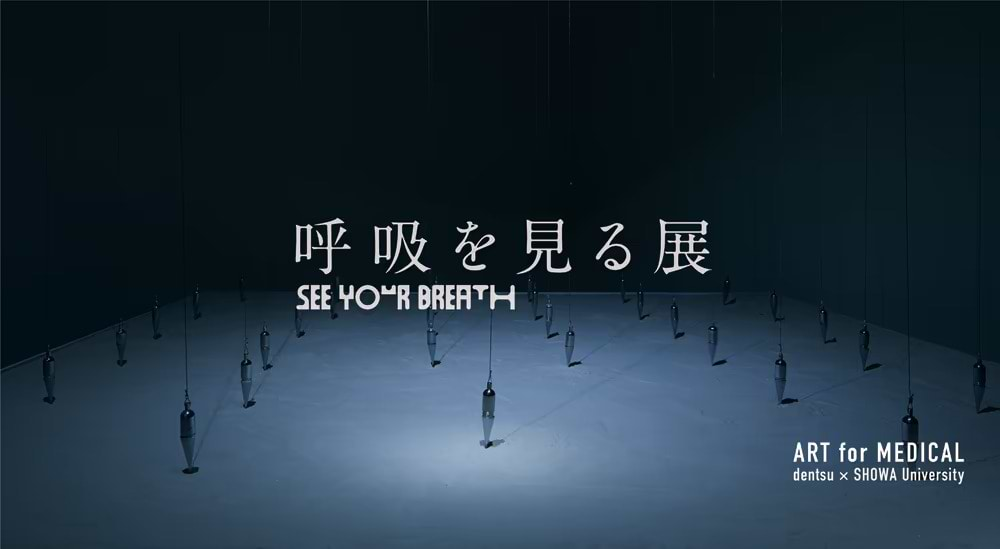

“ART for Medical” is a research project that combined medical care and art. It was promoted by Laboratory of Biological Regulatory Function, Department of Physiology, Showa University School of Medicine and Dentsu Inc. The project aimed to use the power of art to update medical care, making it accessible and enjoyable, and helping to improve quality of life (QOL).

The first challenge we tackled was a media art* installation titled “SEE YOUR BREATH” exhibition, which to visualize breath as a means to help regulate it.

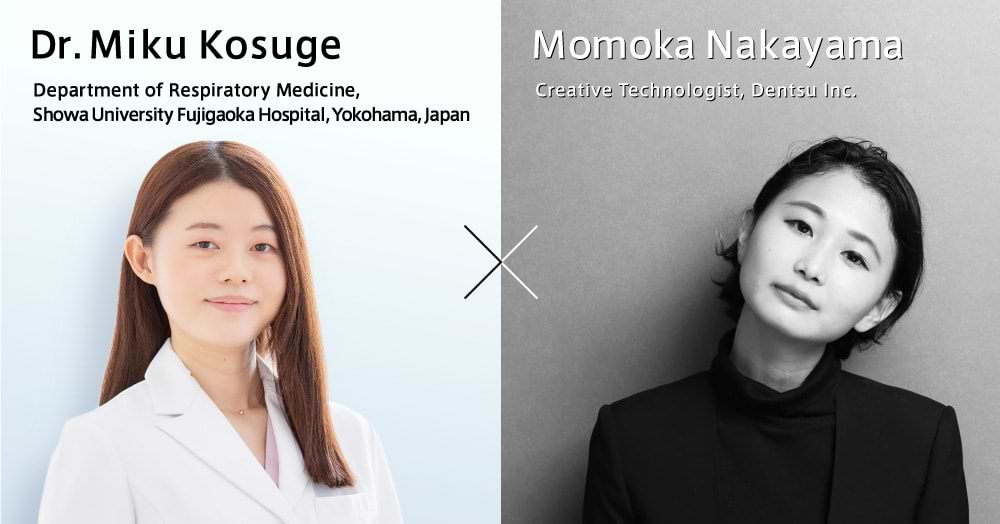

In this article, Momoka Nakayama of dentsu, who was involved in this production as a creative technologist, interviews professor Miku Kosuge, who is both a researcher and a pulmonologist, and who treats patients on a daily basis. We asked about her experience of the exhibition as a project member, and about the possibilities of combining medical care and art from a doctor's perspective.

| * | The installation used digital technologies. |

Exhibition overview

Held at the Showa University Kamijo Memorial Museum through March 22, 2022, the theme of the exhibition was visual pulmonary rehabilitation. The installation was intended to draw attention to breathing and help its regulation by having participants visualize their unconscious breathing.

Art has a place in medical care

Nakayama: With the installation work entitled “SEE YOUR BREATH,” I carefully considered how to visualize breathing and express it as art. Dr. Kosuge, I would like to ask your opinion on this exhibit from your perspective as a medical professional. To begin, what is your area of specialization?

Kosuge: I am conducting research as a graduate student in the Division of Biological Regulatory Function, Department of Physiology, Showa University School of Medicine. I also work as a pulmonologist at the university’s hospital. As a physician, I treat all respiratory diseases, including lung cancer; infectious diseases such as pneumonia; chronic respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); interstitial pneumonia; and allergies, including asthma.

Nakayama: Of the works you saw at the exhibition, what were your thoughts about “SEE YOUR BREATH”, which visualized breathing in the form of a circle?

Kosuge: As the circle got bigger, I could imagine my lungs expanding, which made it seem easier to breathe.

Nakayama: When we spoke to Dr. Masaoka earlier, we learned that he is currently conducting research with the aim of applying this concept in rehabilitation activities.

Kosuge: I thought it could also be applied to respiratory rehabilitation in clinical settings. However, it would be necessary to verify its efficacy on a certain number of people, including those who are healthy. In reality, I think each person will have a different reaction.

Nakayama: It’s interesting that the visualization enables us to see differences in individual reactions. Next, I would like to ask you what you thought about the work “SEE MEDICINE,” in which a pendulum swings in sync with breathing?

A 3D work in which a suspended pendulum moves in time with the participant’s breathing, and a sand image is drawn according to its trajectory. In addition to reflecting the breathing of a participant, the sand image indicates the diverse breathing patterns of the 33 individuals who were monitored.

Kosuge: Being able to focus on the rhythm of my breathing and the movement of the pendulum helped me feel very relaxed mentally. It may also have the effect of improving concentration.

Nakayama: With “SEE MEDICINE,” a pendulum swings toward you when you inhale, and away from you when you exhale. The pendulum moves on the horizontal axis at a constant rate of 12 times per minute, which is the average breathing cycle of a human. If a person’s breathing is stable, a beautiful figure eight is drawn in the sand beneath the pendulum.

Kosuge: Unlike the first work you mentioned, this one visualizes breathing rhythm rather than lung capacity. My impression was that it helped me regulate my breathing rhythm. As you can imagine, the breathing of people with respiratory diseases tends to be shallow and quick. I believe this concept can help guide them to slower, deeper breathing.

Nakayama: Since many people do not have regular breathing patterns, the sand images also take on various shapes. Breathing speeds up and slows down, but never repeats the same trajectory. Misalignment gradually occurs, and some sand patterns ended up looking like flowers rather than figure eights.

Kosuge: There is no rule dictating that we should breathe 12 times per minute, so it is not a problem if the sand images are a bit distorted. However, if you intend to use this as an effective treatment, I recommended that you instruct the patient to try for a clean figure eight pattern as a way of training their breathing to be rhythmic.

Nakayama: What did you think about “Iki-utsushi”?

A work in which paintings depicting emotions, such as joy, anger, sadness, and happiness are linked to a participant’s breathing. Participants experience how emotions depicted in the paintings are transmitted through their breathing.

Kosuge: There’s something visually captivating about a painting that is linked to your breathing. I also thought the idea of the glass fogging up from exhaled breath was brilliant. As with all the works, the movement of the chest when breathing is detected by means of a band or sensor worn on the body, so there is no risk of aerosol droplets, and it was also good that it was conducted in an environment with infection control measures in place.

The Potential of Medical Data × Media Art

Nakayama: With this exhibition, we attempted to communicate medical data related to breathing as media art. From a doctor’s perspective, what kind of art works do you think could be used in the medical field?

Kosuge: COPD and interstitial pneumonia are representative diseases that cause chronic respiratory failure, but the two pathologies are significantly different. COPD is a disease caused by long-term smoking, which results in lung tissue breaking down and expanding, narrowing the airways and making it difficult to breathe.

Interstitial pneumonia is a disease in which the lungs become stiff and shrink for some reason, making it difficult to breathe. It is difficult for patients to understand this difference, so it would be great if we could visualize the stiffness and volume of the lungs through artwork.

Nakayama: In the medical field, a respiratory function testing device called a spirometer is used to observe respiratory volume and the waves of inhalation and exhalation, but this is merely a visualization for doctors to interpret. It seems that art could be used as a method for communicating these figures to patients.

Kosuge: People with COPD or asthma have difficulty exhaling. So, the amount of air they can exhale in one second is an indicator of their condition. Known as the one-second volume or one-second rate, this method is used to assess their condition and classify the severity of their disease.

People with interstitial pneumonia have stiff lungs that make it difficult for oxygen to diffuse within the lungs, and there are tests to measure diffusion capacity. There is a lot of medical data pertaining to breathing besides lung capacity, so I think there are possibilities for using art to aid patient understanding.

Further, within COPD, pulmonary rehabilitation is considered equally important, or even more important, than drug therapy. At present, it is common for patients to perform breathing exercises, such as pursed-lip breathing and respiratory muscle training. They also engage in physical training, such as long-distance walking.

Pursed-lip breathing is a rehabilitation technique that restricts and accelerates airflow, making it easier to exhale when the airway is narrow and exhaling is otherwise difficult.

Both types of rehabilitation depend on patient motivation and physical strength. Thus, the visualization of breathing, as demonstrated with this exhibit, should enable those people who find rehabilitation tedious to enjoy it.

Using Art to Make Healthcare More Accessible

Nakayama: In future, we want to create spaces where people can experience health and health care through art, just before they have a medical checkup. It would be a space providing an opportunity to face one’s own body.

If, for example, it were possible to receive something like a mini-medical exam within the framework of an art exhibition, medical care would become more intimately involved in our everyday lives.

Kosuge: Everyone has a different approach to health: Some people have frequent checkups, while others never come at all. However, access to health screening is important, as some lung diseases can be detected through X-rays, and screenings for smokers can be used to provide guidance on lifestyle-related diseases. I hope this will give shape to some ideas that draw attention to this area.

Related Link

Can Art Help Our Breathing? Possibility of Visual Pulmonary Rehabilitation (Japanese language only)