In Japan, a country prone to earthquakes and other natural disasters, it is imperative that everyone be in the habit of having emergency supplies at hand in case misfortune strikes. Taking one’s own supplies to an evacuation shelter helps make the situation easier for everyone staying there.

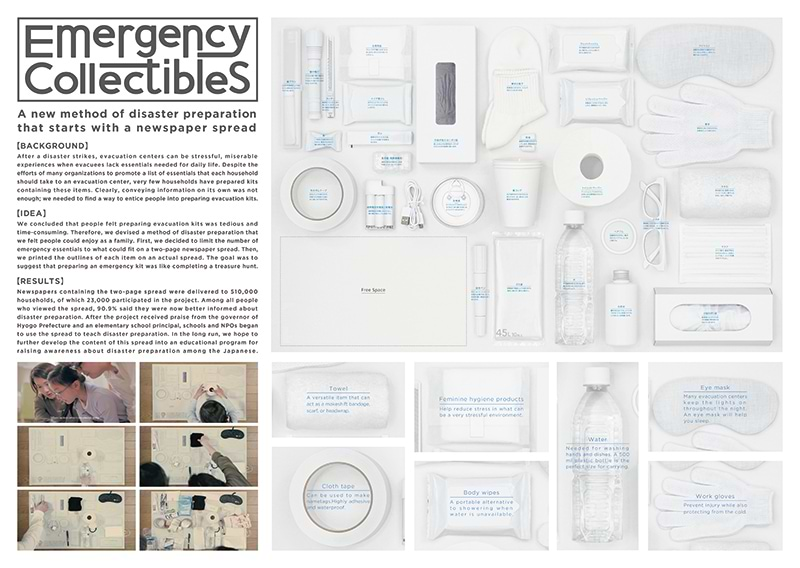

In that context, “Emergency Collectables” was featured in the May 17 edition of the Kobe Shimbun newspaper. Spread across two pages, the newspaper showed actual-size images of items that should be taken to an evacuation shelter. It was designed to encourage people to prepare a bag of relief supplies by first placing them on the corresponding items on the pages. The project has received numerous awards in Japan and abroad, including the Grande for Humanity at Adfest 2018, held in Thailand.

A creative team from Dentsu was involved in all aspects of the project. To learn how the project came to life, and what ideas the creators contributed and focused on, we interviewed the project leader, Ken Akimoto, a member of the Data & Technology Center’s Location Based Marketing Department.

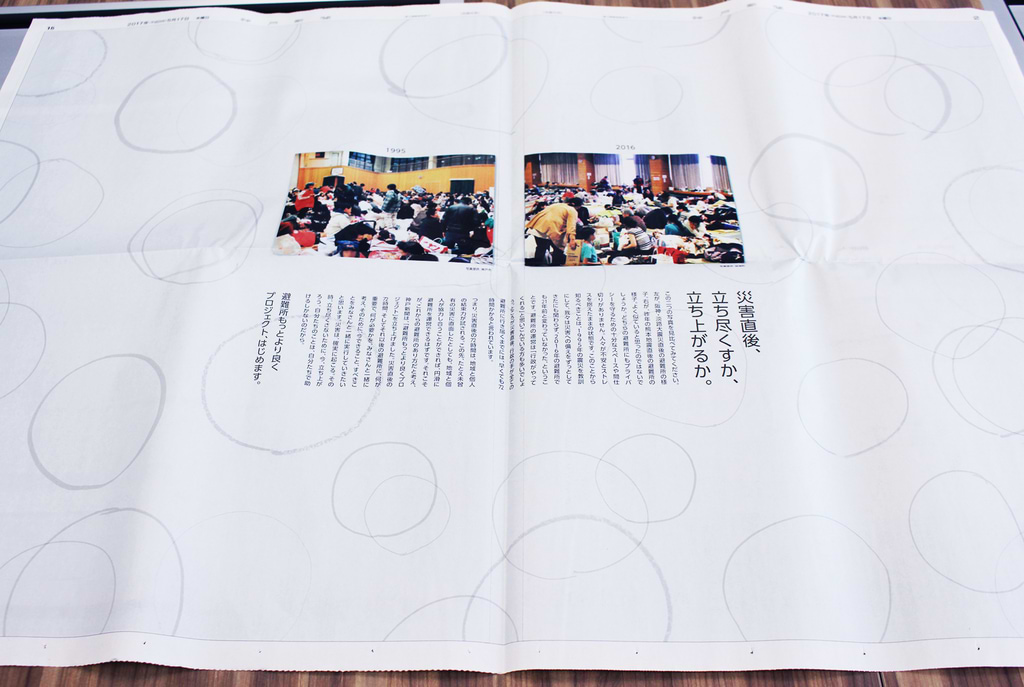

“Two back-page photos, showing problems at evacuation shelters, provide the impetus for the project.”

How did you feel when “Emergency Collectables” received the Grande for Humanity at Adfest 2018?

The Kobe Shimbun Company has been spearheading disaster prevention activities for over 20 years, so I was delighted that the newspaper’s dedicated efforts, together with the ideas of our creative team, were lauded internationally. It was a new experience for me, because I had never paid much attention to advertising awards in the past.

Why hadn’t you paid attention to such awards?

In my job, I mainly analyze data while identifying issues and searching for insights with a focus on finding solutions. I currently work at the Data & Technology Center but, over the past few years, I have been involved in developing solutions based on geolocation information and promoting communication strategies.

Thus, for example, when exploring how an area might attract tourists, I would start by analyzing data on the movement of tourists, before devising the steps it would be necessary to take.

Having worked on many similar projects, I was not competing for the attention of an audience on an expressive level, and so didn’t think about advertising prizes.

How did you become involved in the “Emergency Collectables” project?

It was the Kobe Shimbun Company that had initially considered creating a feature about disaster preparedness on the pages of its newspaper. The company is based in the Kansai region, which was struck by the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995. Ever since, the paper has conducted disaster prevention initiatives.

Dentsu teamed up with the newspaper, and the initial plan was to use newspaper space to show a simulation of human traffic along the major streets that would serve as evacuation routes in the event of a major earthquake. I was asked to join discussions, since I had a lot of experience in handling geolocation data.

As the project began taking shape, however, the news organization said that it wanted to focus on evacuation shelters during disasters, and that led to the ideas that went into developing “Emergency Collectables.”

Why was the focus shifted to evacuation shelters?

Massive earthquakes are common in Japan. Besides the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995, the country’s northeastern Tohoku region was struck by a huge earthquake in 2011, and a major earthquake struck the Kumamoto region in 2016. Evacuation shelters are set up when there is a serious disaster but, in the immediate aftermath, there will often be confusion, which is a major source of stress among evacuees. The Kobe Shimbun Company was particularly aware of that, having had plenty of experience covering evacuation shelters. The company explained that, since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, building standards had been revised, buildings in the area were generally sound, government administrations were working together over a wide area, and disaster prevention campaigns were being conducted by community associations.

Unfortunately, however, the chaos commonly seen at shelters right after a disaster had not really changed. That fact was presented on one of the pages of the “Emergency Collectables” feature.

The main page showed the emergency goods required, and on the back of the page were photographs of two evacuation shelters: one at the time of the 1995 earthquake in the Hanshin-Awaji region, and the other at the time of the 2016 earthquake in the Kumamoto region. Looking at the two photos, one can see that the chaotic situation was essentially the same at both shelters. Consequently, how that situation could be improved was the main theme of the feature.

“Drawing on the advantages of newspapers.”

So, to help remedy the chaos, “Emergency Collectables” encouraged local residents to prepare emergency items to take to a shelter?

That’s right. We learned that the first 72 hours after a disaster are the most important for saving people’s lives. During those hours, police, fire fighters, and local government officials go to help people in the most life-threatening places, so evacuation shelters are likely be understaffed.

Therefore, whether an evacuation shelter can be properly run will depend on the involvement of local residents. Indeed, because the situation is so severe during a disaster, we have no choice but to do things ourselves.

It is, thus, essential for every resident be aware that a disaster could occur any time, and to be prepared. Our project stems from the concept that local residents can take personal responsibility for disaster preparedness.

How did you get the idea to print actual-size emergency items on a page, so that the things could be placed on top?

I had been collecting all kinds of information and data, and then sorting it according to issue. For example, when looking for what irritated people at evacuation shelters, we found that they often complained about noise and the lights being on most of the time. We thought we could help alleviate this discomfort by including earplugs and an eye mask among the items to be packed, even though we thought almost nobody would ordinarily include such things.

From the outset, we knew that very few households in Japan prepare a bag of emergency items. But we realized that, if households did prepare such a bag, living conditions at evacuation shelters would certainly improve.

I also asked my wife and my son, who was in elementary school at the time, what they would want to take to a shelter were we in an emergency situation.

Various organizations have created lists of items to prepare for emergencies. When I looked at these lists, however, I felt that they included too many things, making them unrealistic. One list called for nine 500-milliliter bottles of water, but that alone could fill an evacuation bag.

In my case, if a disaster struck during the day, I would be at work and my son at school, so my wife would have to carry the bag. She told me that so many bottles would be too much for her to handle. When talking with my family about those things, I realized that it was necessary to create a new list.

I thought about what kind of evacuation bag was manageable for a person, and narrowed down the list to a minimal number of items that seemed realistic. My wife said that she could handle the emergency items that finally appeared in the newspaper.

So, the original ideas came from discussions with your family?

Yes. In fact, an important aspect of Emergency Collectables is that it encourages family discussions about preparing for a disaster, as everyone collects the items. The household members become much more aware of disaster preparedness by doing so. When that point was commended by an Adfest judge, I was happy that our intention had been clear.

The things needed when staying at an evacuation shelter differ according to family. The items shown in the newspaper should be regarded as no more than examples. To have readers recognize that and think about the items they themselves need, we included on the page an empty area marked “Free Space.”

Could you comment on the fact that the project proposed a new use for newspapers?

When thinking about the project, everyone on our team talked about drawing on the advantages of the newspaper as a medium. Among the benefits, a newspaper is made of paper, so readers can keep the content and, since broadsheet newspaper pages are large, items can be shown in full size. Further, because newspapers are printed using ink, two types of content can be shown on the same page by using a special kind of ink that changes color.

Since it is important to limit the size of an evacuation bag, items should be selected carefully. Arranging the items on the page led to many of our ideas.

“Using data to probe problems; seeking solutions.”

Have any responses to the feature impressed you?

The principal of an elementary school explained to students in a morning assembly that everyone should use “Emergency Collectables”, and that doing so is important. An NPO has also used it in workshops.

I was overjoyed by those responses. In the future, it would be ideal were “Emergency Collectables” used in elementary school disaster preparedness lessons. Once a year, if school children in a certain grade would take it home as a homework assignment and prepare an emergency evacuation bag together with their family, I am sure that awareness of disaster preparedness in their whole community would grow.

I was delighted to receive the advertising awards, of course, but my goal is to offer real solutions. That is to say, to the extent that “Emergency Collectables” can encourage every member of a community to take ownership of the issue of disaster preparedness, the closer we will come to reaching the goals of raising awareness of disaster preparedness and improving conditions at evacuation shelters.

So, for me, it is important that whatever work I do should eventually lead to such solutions.

Please tell us more about how your work could lead to solutions

Analyzing data, for instance, enables us to illuminate a problem, but does not solve it. The key issue is how we go about solving the problem we have identified. Thus, instead of just analyzing data, I want to devise strategies and communication tools that will provide solutions to such problems.

At present, I am involved in a campaign to promote the city of Hyuga as a town for surfers (please refer to the promotional website for more details (English and Japanese): http://www.phew-hyuga.jp/). The project is intended to encourage more people to move to the city, which is located in Miyazaki Prefecture. The city’s beach is a popular surfing spot, and by highlighting the fun of surfing, the campaign is trying to attract new residents.

Just as in other projects, I started by using geolocation and related data to analyze the movements of people who come to surf along the coast of Hyuga and Miyazaki cities. I looked at the reasons that people travel there from big cities that are far away, like Tokyo and Osaka, and which routes they take. And I also identified which areas were competing with Hyuga for surfers from such cities. Based on an analysis of that data, we designed a communication strategy to reach surfers outside the prefecture and encourage them to move to Hyuga.

Thanks to a promotional video we made for the project, Hyuga attracted attention in Japan and the number of surfers visiting the city went up. Nevertheless, it is not that easy to increase the number of people moving there. People who consider moving to Hyuga are concerned about the jobs available. It is a small regional city, so the range of available jobs is more limited than in big cities.

We recently began devising a plan to increase the number of new jobs in Hyuga. Located in a beautiful natural setting, the city is well-known nationwide for its cedar wood. Were that wood used to make finished products for sale in large cities, Hyuga could be more prosperous. Yet, we heard, the lumber is being shipped out mainly for use as building material.

At the same time, we considered the lifestyle of surfers, who tend to like natural materials, do-it-yourself projects, wood interiors and items made of wood.

Therefore, I believe, solutions to the city’s need for new residents could be provided were locally grown cedar used to produce the furniture and interiors that surfers like; such products were sold in large cities; and systems were put in place enabling new residents to become directly involved in those activities.

Were local lumbermen teamed up with good designers, it may even be possible to create a new local industry.

Perhaps it is obvious from my explanation, but I tend to mull over possible solutions, even when not asked to do so. As I solve a problem, more challenges arise, so my work is never done.

“I want to connect our projects to consumers’ lifestyles and get people to take action.”

Your example implies that, for solutions to materialize, a local industry must be created. Given the huge project scale, it seems difficult to describe your job in a few words.

I guess you are right. I analyze data, produce things, and create narratives. Maybe the closest job description would be communication design, since I am very conscious of that way of thinking.

Despite the remarkable technical advances nowadays, if companies only focus on gaining a technical edge and engage in a battle over technology, their output will not be very useful for anyone.

Instead, things that people regard as useful in their lives are important, so the question is how to create things that can become part of people’s lives. We should make use of technology for that purpose. I learned that principle at Dentsu, and I regard it as extremely valuable.

Does “Emergency Collectables” reflect your communication design?

Yes, communication design was reflected in the elements of “Emergency Collectables” that encourage people to try it out, and that stimulate family discussions.

Moreover, from the planning stage of the project, we aimed to have the material used at schools as a homework assignment after it had appeared in the newspaper. We knew that a newspaper feature inviting readers to prepare evacuation supplies would be ignored or forgotten by many adults because they are busy. But if it was used as a student’s homework assignment, parents would make some time for it.

The user experience is important in any kind of project we handle. That means the issue is whether we can successfully connect our project design to the lifestyles and regular habits of consumers. If the project design is detached from their lives, we will not be able to get them involved, and people will not take action.

Technology-based projects linked to people’s lives are novel

By combining data and creativity, I hope to inspire people to take action and help change things for the better. At Dentsu, I plan to continue searching for solutions using geolocation data.

Ken Akimoto

Data & Technology Center

Location Based Marketing Department