My name is Ryosuke Sone, and I am a member of Dentsu Lab Tokyo, where I mainly work as a video director and occasionally as a planner and designer.

Due to the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, watching sporting events remotely is now a necessity. In this article, however, I want to look back on a Dentsu project that was intended to greatly enhance the spectator experience inside the venue.

Personally, I don’t particularly like going to watch sporting events. I don’t dislike playing sports, but watching sports requires some knowledge about the match. Even if we know the rules of the sport, we cannot fully enjoy or appreciate the match unless we know the players, the strategies and strengths of each team, the context leading up to the match, and so on. Indeed, the more popular the sport, like baseball and soccer, the more we may be ridiculed if we don’t know anything about it. Here in Japan, if I were to ask who Rui Hachimura (a Japanese professional basketball player now playing in the NBA) is, people would probably accuse me of not keeping up with the news. That would be very embarrassing (although I admit, I don’t follow the news).

My disappointing memories of spectator sports

I attended Fujieda-Higashi High School, which is well-known in Japan for its soccer team. When I entered the school, I had to buy soccer cleats and shorts. I also remember playing soccer most of the time in our physical education classes. My school’s team was a championship contender, so I often went to the games to cheer it on, which I genuinely enjoyed. Watching some of my good friends run around the big field made it easy for me to get caught up in the excitement. I really wanted our team to win and share the joy of victory. I felt united with my school’s supporters at the stadium, and could experience the drama of the game on a personal level.

Those experiences were very different than what I had when watching matches of the J. League, Japan’s professional soccer league. I didn’t know the players going for the ball, and in such a big stadium, I couldn’t see the faces of the players unless I used binoculars, and even the numbers on their shirts were hard to see. Furthermore, I didn’t know the circumstances surrounding the matches unless my friends explained that to me. I also recall how the wind was stronger and colder than I had expected. All of those things made me wonder whether it would be better to just watch the game on television.

Discovering the great complexity of fencing

With those memories still in my mind, I helped stage the finals of the Japan national fencing championship about three years ago. It was a new production for Fencing Visualized, a project jointly created by Dentsu Lab Tokyo and a Japanese company called Rhizomatiks. The project’s latest videos are available online.

At that time, fencing seemed to me to be a very dynamic sport, and various techniques were being used to promote fencing matches to a broader audience in Japan, capitalizing on Yuki Ota’s Silver Medal victory at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

To prepare for the production, I started studying fencing by watching a match on YouTube.

https://youtu.be/M7F4bRsqyCI

Honestly, I did not understand anything that was happening. I couldn’t even figure out who was on the attack. Mystified, I gave up watching after just one match and closed the web browser. In my mind, however, I could hear the god of advertising whispering, “The mission of advertising is to make people like the product.” I am grateful to the god of advertising for reminding me of that.

Taking off the storm trooper masks

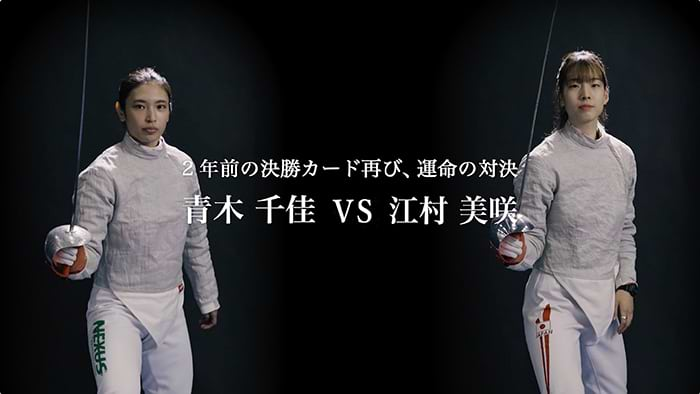

As part of the project, we began by creating brief video profiles of the competitors prior to their match. That was because, as you can see by watching fencing, the competitors wear a mask while dueling, so their demeanor and appearance are hidden, just like the storm troopers in Star Wars. In other words, nobody knows who anyone is. By watching the profiles first, however, viewers would be able to better understand and appreciate the individual styles of each competitor.

Actually, although they are rivals, the fencers we profiled have very good relationships with each other. The fencing community is relatively small in Japan, so the country’s top fencers train with each other to improve their skills. Some are from the same school, while others are siblings or even married couples. Some are also coached by a parent. Since they have formed such beneficial relations over many years, knowing more about the competitors makes their matchups all the more intriguing.

https://youtu.be/7VRFdsReJPs

In the lead-up to the day of the competition, I had learned a lot about the sport and greatly enjoyed watching fencing matches. I admit that my knowledge of the rules was still a little shaky, but I can enjoy watching sports as long as I know the competitors. (Similarly, The Avengers is not such an interesting movie unless you know about the relationships between the characters.)

Moreover, I recognized the issues we needed to tackle in the project going forward. I thought about my own experiences with spectator sports, especially not knowing the players, not understanding the match, and preferring to watch games on television. On that basis, I framed our three main tasks as follows.

- Provide more information about the athletes

- Explain the rules and techniques of the sport

- Make the spectator experience better than TV

1. Providing more information about the athletes

A year after the project started, we made numerous videos available on social media to allow people to get to know the fencers and see their amazing skills. In the videos, we interviewed the competitors, documented their training sessions, and captured them behind the scenes to give a glimpse of their personalities. That created excitement leading up to the day of the championship finals.

At the venue, we installed a large monitor to display each competitor’s profile photo and various real-time stats during their match-even their heart rates. We designed it to reveal each fencer, just as Robert Downey Jr.’s earnest character was shown inside his mask in the movie, Iron Man.

2. Explaining the rules and techniques of the sport

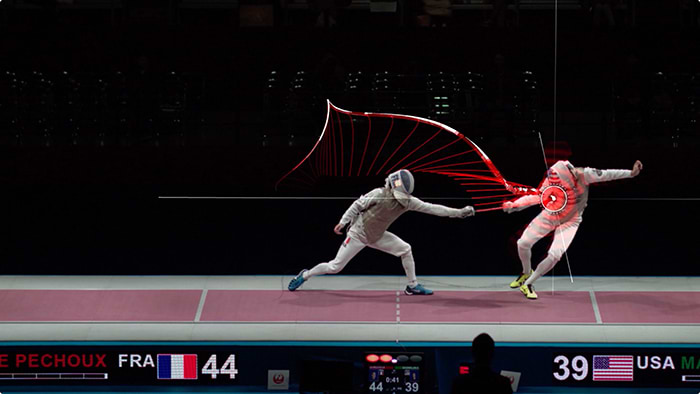

The rules of fencing are complicated, but we carefully explained them numerous times through videos, a website, and at the venue itself. Even if one knows the rules, however, the fencing swords move so fast that they often cannot be captured by television cameras shooting at 30 frames per second. Therefore, the Fencing Visualized project used technology to display the paths of the sword tips, allowing viewers to see the competitors’ tactics and offensive and defensive techniques.

“Fencing tracking and visualization system” Rhizomatiks

https://youtu.be/D6DTYeLW3C0

The Fencing Visualized project has continued to evolve, and its technology has been deployed in actual matches since last year. Now the technology not only captures the paths of the sword tips but also the motions of each fencer’s body, allowing their movements to be reproduced in 3D.

3. Making the spectator experience better than TV

We also wanted to make it more fun to be at the venue by incorporating various ways to raise the entertainment value of the fencing events. They included a LED light show, music played by DJs, and a dance performance against the backdrop of a transmission screen and laser lights. Indicators of applause and cheering volume were shown on a screen to capture the excitement in the venue, and sub-bass speakers were used to fill the venue with a deep vibration sound when the fencers’ scores were displayed. During the intermissions, fun interactive games were organized in the spectator seating area. If all of this is hard to imagine, the following video provides a snapshot of the events.

Highlighting the fun and fascination of sports

Fencing is a sport that has never generated much excitement in Japan. At the championship final, however, loud cheers were heard throughout the venue by midway through the event from the enthusiastic crowd. I think that was largely the result of the various technologies and innovations adopted by the project.

On social media, such as Twitter and the Japanese video streaming website, AbemaTV, many people who watched our videos said the innovative technologies for capturing fencing were highly interesting. Those who are not core fencing fans expressed strong interest in the sport after watching for the first time, and many were very impressed even though they didn’t know the rules of fencing. As a casual fan, as well, I was really happy to see those reactions.

In the end, after creating various content designed to arouse interest in fencing, I discovered that the sport itself is really fascinating. Naturally, the best way to experience the drama of fencing is to see it for real. We can move beyond content and capture the imaginations of viewers by showing them the fencers’ personal backgrounds and many years of training. Sports are truly amazing, as everyone already knows, and I hope that people continue taking an interest in fencing.

Ryosuke Sone

Videographer

Planner

Designer

CDC Dentsu Lab Tokyo