Analyzing recent surveys to understand the sustainable lifestyles of 12 nations

In July 2021, Global Business Center, Dentsu inc. and Dentsu Institute jointly conducted a survey, “Sustainable Lifestyle Receptivity Survey 2021”, in 12 countries (Japan, Germany, UK, US, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam).

In the second report of this three-part series analyzing the survey results, we present an online discussion with Yu Kato, who launched the web magazine “IDEAS FOR GOOD”, and the web magazine’s editing staff, Motomi Soma. Rie Tanaka, Global Business Center, Dentsu Inc. and Seiko Yamazaki of Dentsu Institute interviewed the two guests.

Yu Kato (Founder and CEO, Harch Inc.)

Founded Harch Inc. in 2015. Launched “IDEAS FOR GOOD”, a web magazine introducing socially good ideas from around the world.

Recipient of the 1st Journalism X Award in 2020.

Motomi Soma (Harch Inc.)

Editing staff of the web magazine “IDEAS FOR GOOD” and “Circular Yokohama”.

A Generation Z who joined Harch Inc. in 2021.

Seiko Yamazaki (Dentsu Institute)

co-authored "Japanese Way of Thinking: People in the World: What You Can See from the World Values Survey" (Keiso Shobo) and others.

Rie Tanaka

Global Business Center, Dentsu Inc.

dentsu Japan Sustainability Development Office, Dentsu Group Inc.

Responsible for global research and PR related to sustainability

| <Table of Contents> |

|---|

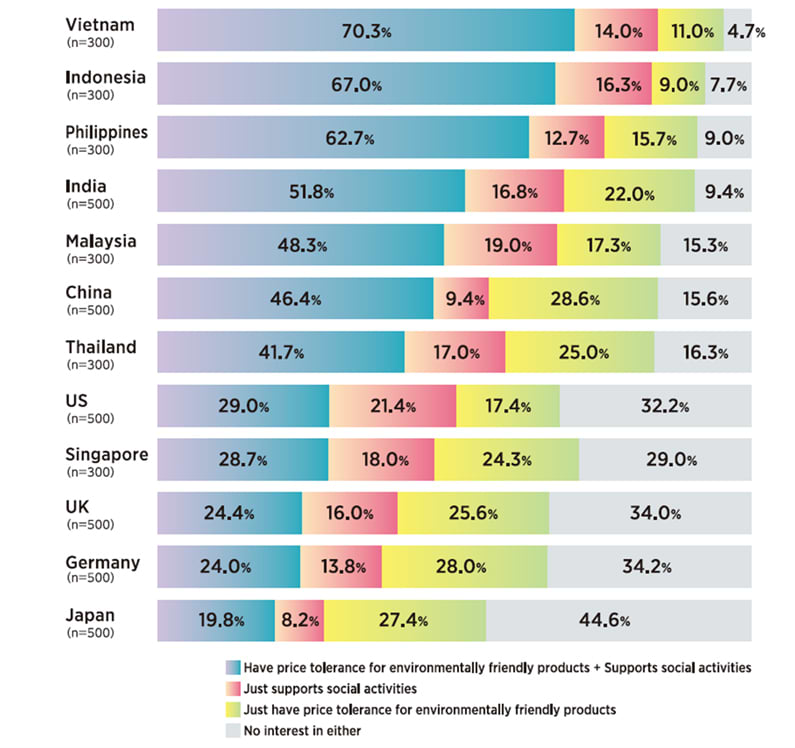

Why people in ASEAN have a high sense of awareness and concern for environment-related consumption and social activities

First we’d like to look at both environment-related consumption and social activities (donations and collecting signatures). Both activities are widespread in Asia, except in Japan and Singapore. In Germany, the UK, and the US, 30 – 40 per cent showed no interest in either activity, a rather high percentage. Of course, there is a characteristic tendency for people in ASEAN, China, and India to respond positively to surveys. Also, the surveyed subjects tend to be residents in larger cities who belong to a higher income segment and have a high sense of social awareness. These factors could have influenced the survey results toward showing a higher score. However, there is indication that there is more to the story.

For instance, the World Giving Index 2021 released in June (which gives figures about how often the respondents did volunteer work, gave donations, or helped others in the past month) showed that Indonesia ranked number one, while Japan ranked 114th and was at the bottom of the list.

While the scores of China, India, and Vietnam went up significantly, the US and Germany were among the countries where the scores went down. Japan could learn about rule making and product development from Europe and the Americas, and gain hints from Asia about raising the sense of mutual help. Kato-san, how did you interpret the results of the survey?

Kato: There were no surprises there. I expected that Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam would score high on environment-related awareness. I keep in touch with local NGOs and I have taken part in tours visiting these areas, and I felt a high sense of social interest especially among the young generation. These countries deal with social and environmental issues on a daily basis. Streets are littered with waste, and there are many waste-pickers (people in developing countries who go around waste disposal sites to collect items they can sell). An Indonesian social entrepreneur once told me, “If we leave it to the government, the environment won’t change. We want the developing countries to speak up for us. We need their help spreading information in English about our waste-filled rivers in Indonesia.” Facebook and Instagram use is popular, and I feel that their activities take into consideration the global trend as well.

Why do you think the interest in consumption and social activities is low in the UK and Germany where movements in these areas are advanced?

Kato: The environmental measures in Japan, Germany, and the UK are advanced and the system is well in place. Even if people’s interest is low, there is hardly any garbage left on the street. Although there is a debate about garbage incineration, Japan has one of the most advanced systems of collecting and incinerating garbage. For that reason, Japanese people do not feel so guilty about throwing away garbage, and this makes them less concerned about taking direct action in consumption and social activities.

Also, the survey showed that Americans take interest in social issues since inequality and racial discrimination are serious problems (refer to the previous report). This is an indication that people tend to become interested in things that are happening right in front of their eyes.

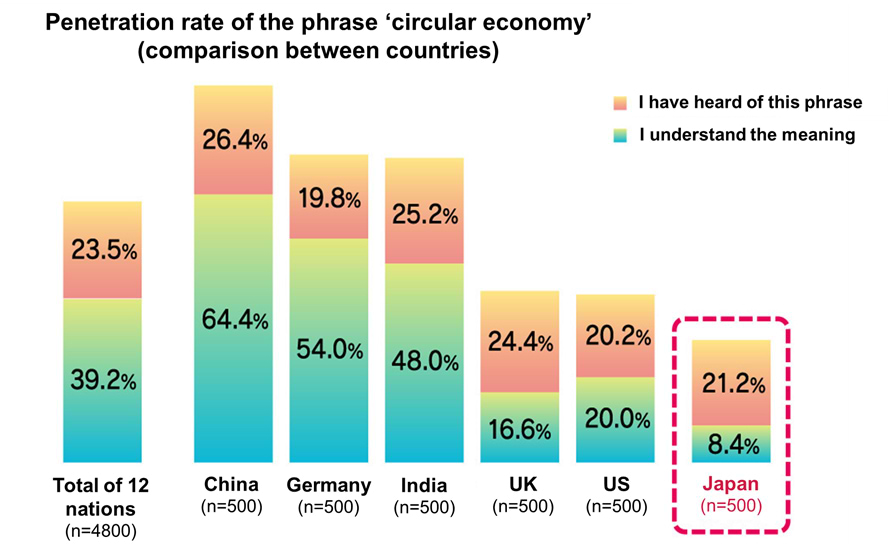

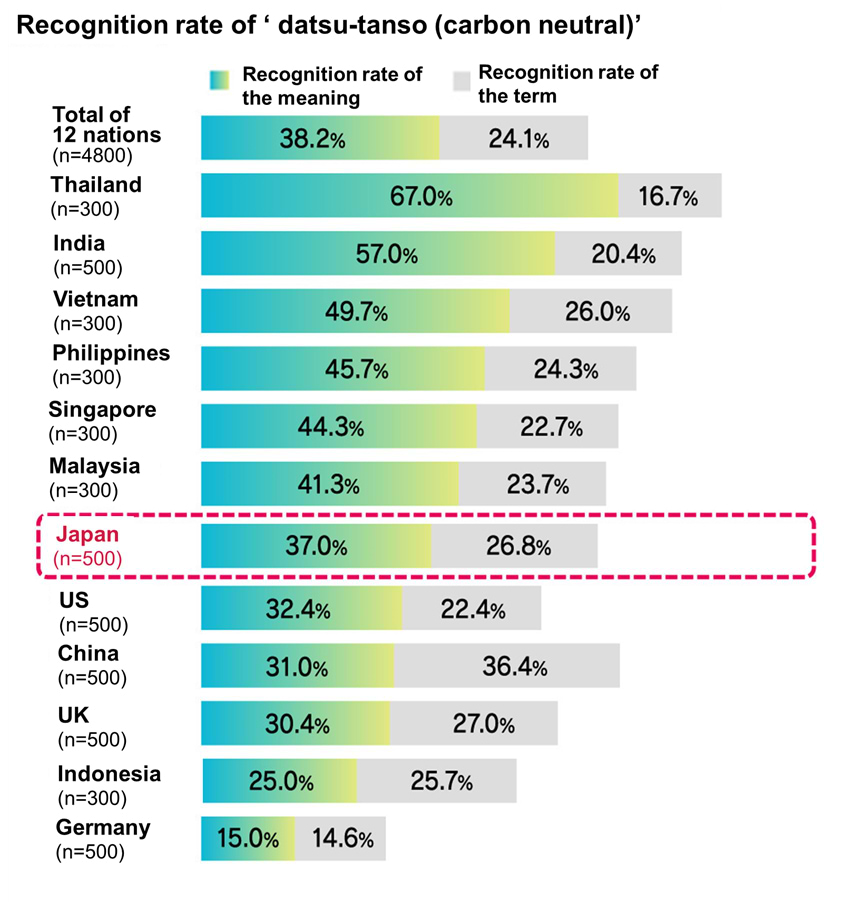

Terminologies that help personalize a circular economy and a recycling society

Kato: When surveying people’s recognition of terminologies, the response may be different if you use the term ‘circular economy’ in English or in their native language. What language was used for the survey in China?

In China we used Chinese and in Japan we used Japanese. In other countries as well, we phrased the terminologies in the local language.

Kato: China was the first nation in the world to pass the Circular Economy Promotion Law in 2008, so perhaps they are familiar with the phrase in Chinese. The Japanese also are more familiar with the Japanese term of ‘JUNKAN’.

In Europe, there is discussion to shift from a circular economy to a circular society so that the idea of circulation is not restricted to resources or the economy but spreads throughout society. We checked and found that the Ministry of Environment in Japan had been using the phrase ‘recycling society’ from the beginning.

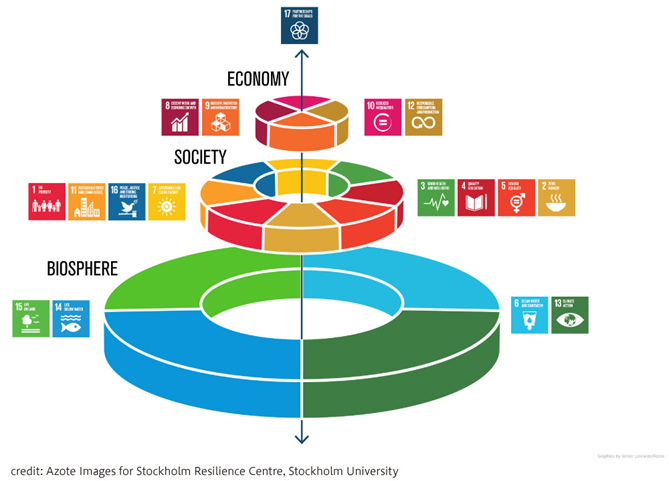

If we look at the SDGs wedding cake (*1) the largest portion is ‘environment’, followed by ‘society’ and ‘economy’. Between ‘economy’ and ‘environment’ lies the issue of ‘society’. In terms of including ‘society’ to ‘environment’ and ‘economy’ to understand and deal comprehensively with ‘circular’, Japan’s concept of a ‘recycling society’ may be one step ahead than the concept of a ‘circular economy’.

It is not easy to personalize foreign terms such as ‘SDGs’, but the phrase ‘JUNKAN’ in Japanese seems more familiar to the Japanese and would be easily embraced by the public sector and its citizens. There is a need for a discussion by the media about which is better sounding for PR purposes, the phrase in English or in Japanese.

- = SDGs wedding cake

An illustration of the 17 SDGs shaped like a wedding cake. It shows that the human society and the economy are built on the biosphere foundation.

Relocating carbon to achieve zero emission

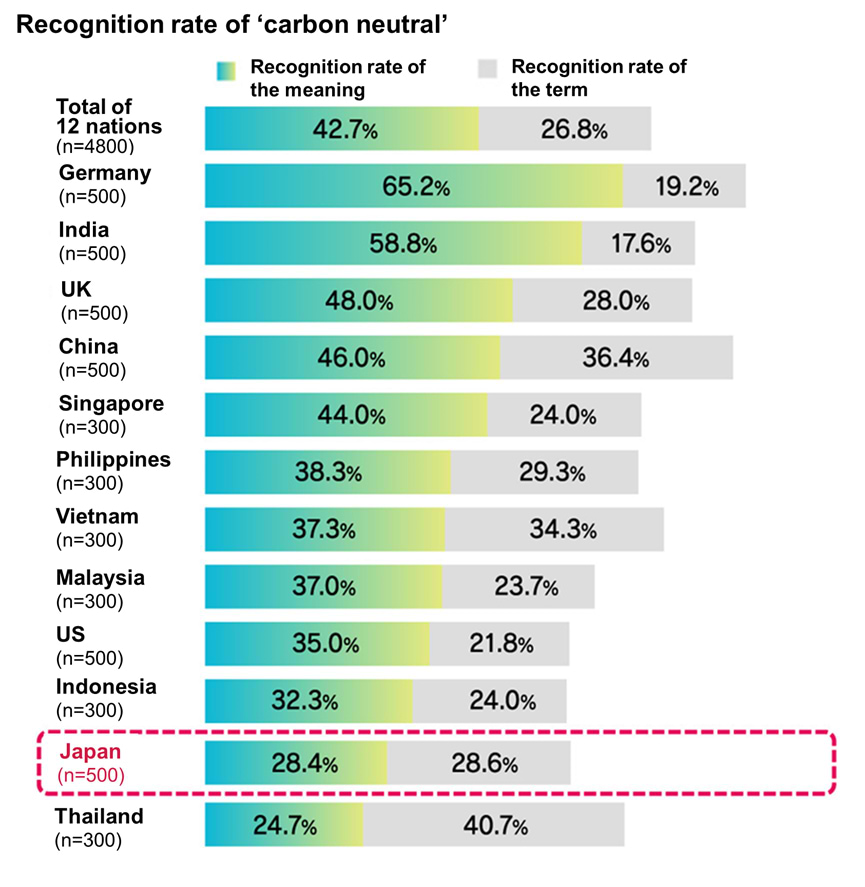

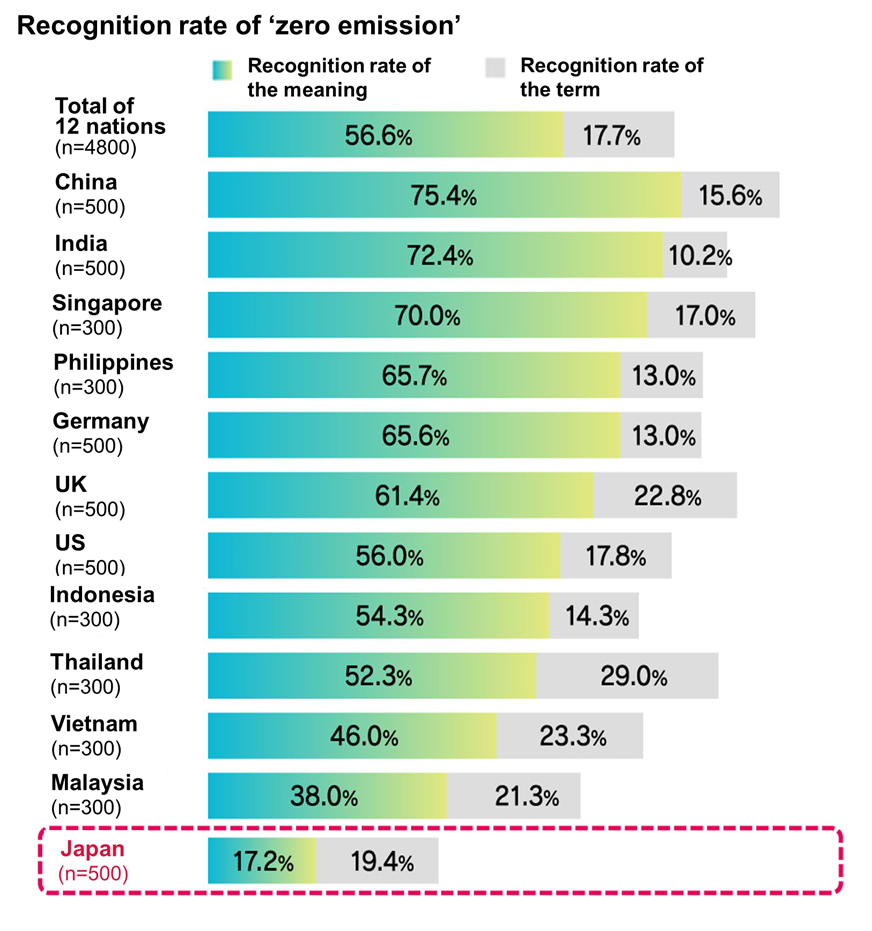

What do you think about the widespread use in Japan of the phrase ‘carbon neutral’ in Japanese? In other countries, the phrase ‘zero emission’ is used. Does the difference in the phrases used affect the attitudes towards promotion of the movement?

Kato: The English phrases ‘zero emission’ and ‘carbon neutral’ are fine, but I think using ‘Decarbonization’ is a bit risky because ‘carbon’ could be interpreted negatively.

There is an expression: “Carbon is not a problem; the problem is carbon is in the wrong place.” Since organic matters, including humans, cannot survive without carbon, the circulation of carbon is important. The problem is where carbon exists. Carbon is primarily found under the ground, but when it is released into the atmosphere, it becomes a problem. Instead of labeling carbon as ‘bad’, it is important to accurately explain the idea of circulation. The same goes for ‘plastic reduction’. The image of all plastic being bad makes us think we should reject all plastic. The terminologies we use influence our attitude and actions. At the same time, the Japanese phrases are easy to understand, so the positive side is that they help encourage people to take action. Therefore, we can’t say it’s all bad.

The next phrase that will come after ‘sustainability’

Kato: Talking about terminology, some think that using the word ‘responsible’ instead of ‘sustainable’ would increase our commitment. Sustainable could be interpreted as having no correct answer, so there is a risk that it may look like the issues are being tackled when nothing is actually being done. Responsible, on the other hand, is an attitude or approach, and there is a strong will behind it. In Japan, though, the term ‘sustainability’ is just starting to spread, so we shouldn’t reject the expression so easily.

A similar debate exists with the term ‘SDGs’. There is risk that it could be all talk but no action. If we raise the standards too high, many companies may not be able to keep up. I think we would see more progress if we could be tolerant and have more companies involved that think they can make a contribution, no matter how small that is. By the way, there is some talk about what phrase will emerge after ‘sustainable’, but it hasn’t been fully identified. What do you think it would come down to?

Kato: The direction in Europe points to ‘wellbeing’ as a big theme. The phrase ‘wellbeing economy’ is being used in Norway, Finland, Iceland, Scotland, and New Zealand.

‘Wellbeing’ is becoming the focus as an ultimate goal of corporations and society in Japan too, as seen in the phrases ‘wellbeing management’ or ‘Gross Domestic Wellbeing = GDW’ replacing GDP.

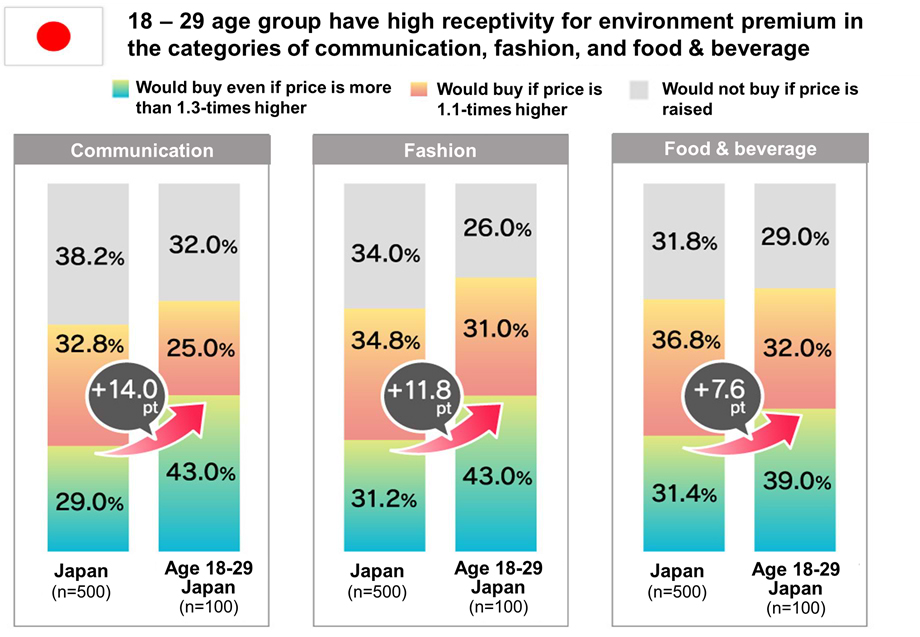

The reason Generation Z accept environmental premiums

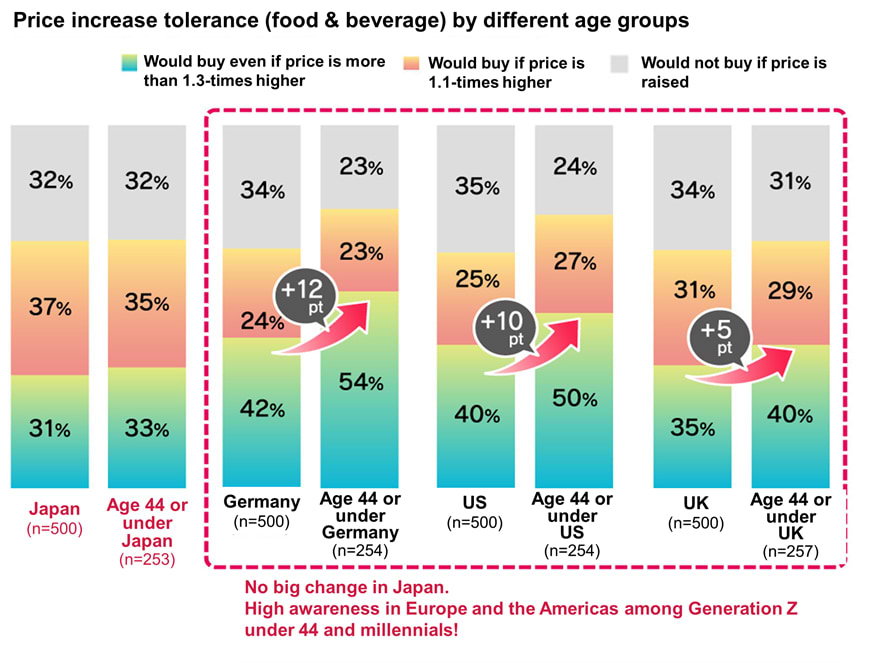

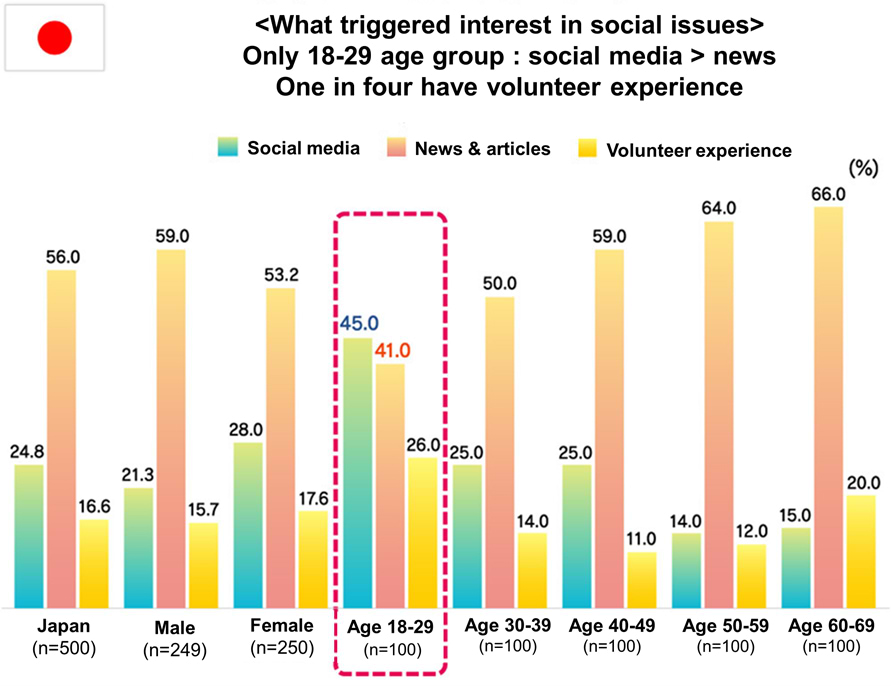

In the survey we asked how much price increase would be acceptable for different products with low environmental burden. The 18 – 29 age group responded that they would be tolerant for higher prices in the categories of communication, fashion, and food and beverage. Do the young select sustainable products even if they are more expensive because they feel it is cool to do so?

Soma: That might be part of the reason, but there are also many who do care a lot about how inexpensive the product is. Many people have inherited their parents’ values that, except for certain luxury items, less expensive is better. A lot of Japanese companies have also made good quality products and services conditional on making efforts to keep the price down. A lot of young people are also under the belief that the products they buy should be inexpensive. However, there are some who search social media for substantiation on “What does it mean that the price is cheap?” or “Do people know why the price is increased?” By visualizing their findings on social media, the overall awareness and understanding could increase.

Kato: The figures for the 20s and the 60s are high, which could be an issue of disposable income. The purchases made by young people in their 20s may actually be paid by someone else, or the actual price of the product or service could be cheaper in the first place. They may be less sensitive about prices than the generation that is in the middle of raising a family.

Actually, in Germany, the US, and the UK, the survey shows that the receptivity for a price increase for ‘food and beverage’ sharply increases among millennials in their 30s, and a high price range is accepted by those aged 44 or under. Only in Japan do the results form a U-shaped curve (the figures are high among the 20s and 60s, and low for those in their 30s, 40s, and 50s). We also asked about happiness and hopes, and again the results form a U-shaped curve. When we talk about spare energy, we can be referring to a surplus in economic power, physical energy, or mental capacity. In addition to disposable income, I believe that mental capacity also has a considerable influence on the desire to consume environmentally friendly products.

Why Generation Z are actively involved in social activities and volunteering

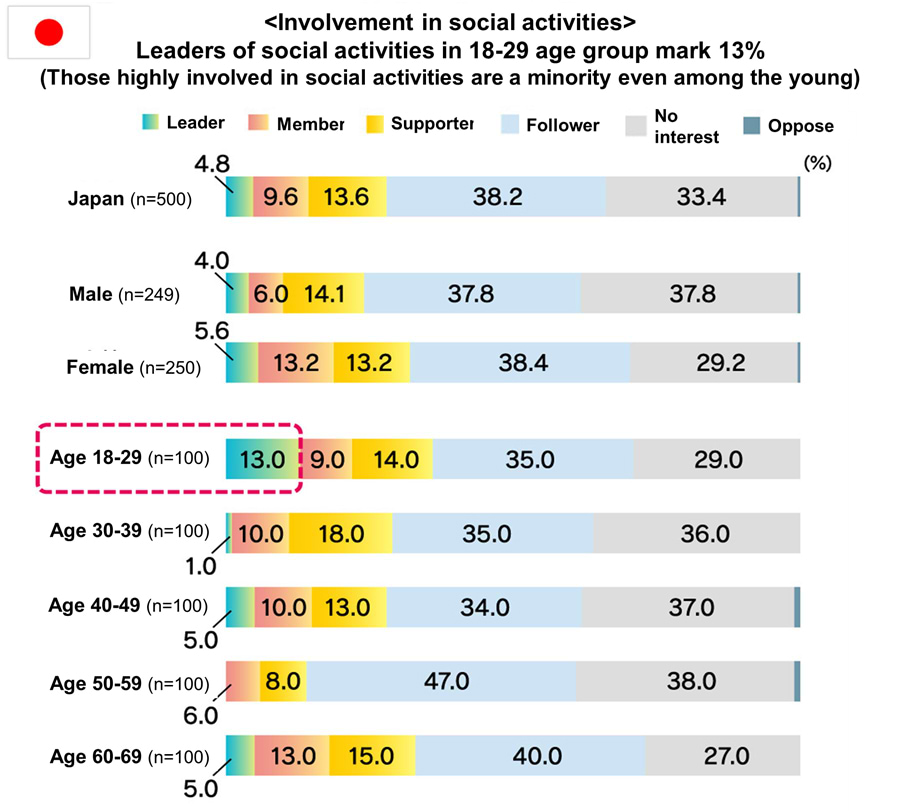

Leaders of social activities are found most in the 18 – 29 age group. As mentioned at the beginning, Japan is ranked at the bottom for people involved in social activities such as volunteering, but this 18 – 29 age group has a high interest in social issues triggered by volunteer activities. This could be attributed to the fact that after the Great East Japan Earthquake, universities started to give out credits to students for volunteering. Is volunteering still common among university students?

Soma: Again, it depends on the individual whether or not he/she develops interest, but I think that it has become easier to get involved in volunteer activities because the student support office at the universities recruit volunteers, and students post their volunteer experience on social media too. The majority of students wish to work for a company or an organization that plays a meaningful role in society, and it is only natural for these students to be engaged in volunteer activities.

In the past three years or so, global warming has caused massive flooding in Japan, and natural disasters are becoming a real threat to people today. Each time there is a natural disaster, student volunteer teams and fund-raising groups are formed, and such movements are very active in recent years. In some countries, volunteering is mandatory in junior high school and is an integral part of education. It is effective to educate children about volunteering from an early age.

An immature society generates a spirit of cooperation and trust

Ever since the world has had to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, priority has been given to publicly beneficial acts or policies in Asian countries. However, only in Japan have we seen a shift to prioritize personal satisfaction. In general, we found that personal satisfaction was prioritized in economically advanced countries. (Refer to the previous report in Japanese.) Hypothetically, it may be because “when we gain economic stability, we become conservative in order to maintain that stable state”, or “we cannot expect mature countries to change in the future, but Asian countries have a large proportion of young people and are still developing economically so it is easier to unite under the belief that there is a better future ahead.” Can you offer other reasons?

Kato: This was a surprise. First of all, I think that Japan does not trust the public sector and has low expectations, so they think they have to do something themselves because they are worried that the government will not be able to protect them.

Even if we know that economic success leads to selfish behavior, data shows that everyone in Asia is obsessed with economic development. In Japan, too, people can understand the economic anxiety of losing their job to AI, but cannot see that one in every seven suffers from poverty.

It would seem that whether they give or receive, people would be happier if they are voluntarily generous to others rather than having taxes uniformly imposed. What is the key to creating a ‘For Good’ society? A higher expectation for the future? Or raising each individual’s level of hope or imagination?

Kato: I think the long-term vision of the nation plays a huge role. In Japan, the government does not make it clear whether the objective is economic growth, or if it is the wellbeing of the people based on the wealth or fulfillment of factors other than ‘growth’. Once the Japanese government stated its vision to achieve the SDGs by 2030 and to achieve zero emission by 2050, we saw that many corporations were serious about making changes to help achieve those goals.

When we see a long-term vision ahead, we feel safe to make investments. Europe presents a 30-year vision that encourages the society as a whole to move towards that direction, and that is the basis for trust to develop. It doesn’t matter whether that direction is right or wrong. A clear vision generates trust, and that gives people comfort and hope.

Soma: Many European countries tend to have a sound and extensive social security and welfare system to protect people who could not keep up with competition. In order to create a ‘For Good’ society, Japan must study those countries’ systems and revise the budget allocation of social welfare. On a personal level, people should first take care of oneself and think about one’s own wellbeing. This will then lead to accepting others. The concept of “IDEAS FOR GOOD” is to focus on solutions, not the issues, so I hope we can create a platform where ideas that lead to solutions are born, and to share those solutions.

Economic growth is important, but people’s awareness or attitude is also a big factor. Asians take a more spiritual approach rather than solving issues logically. For example, “Feel a connection without drawing a line between self and others,” or “Do not judge but do what feels right, and don’t worry if you fail.” There may be a breakthrough on a personal level as well as a national level if we can leverage wellbeing that values resilience instead of logic. This survey actually asked about personal and national wellbeing, but we haven’t fully analyzed the results yet. We hope we can gain more insight from this angle through further analysis. Thank you very much for your time today.

| 【Survey details】 |

|---|

| Title: | “Sustainable Lifestyle Receptivity Survey 2021” |

|---|---|

| Survey method: | Internet survey |

| Survey conducted by: | Dentsu Inc. and Dentsu Institute |

| Survey period: | July 8 – 20, 2021 |

| Countries surveyed: | 12 (Japan, Germany, England, US, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) |

| Survey samples: | 4,800 |

| Subjects surveyed: | Male and female; aged 18 – 69 In the six ASEAN countries, 300 male and female aged 18 – 44. Japan 500, Germany 500, UK 500, US 500, China 500, India 500, Indonesia 300, Malaysia 300, Philippines 300, Singapore 300, Thailand 300, Vietnam 300 |

The percentages have been rounded off to the first decimal place, and the total therefore will not necessarily add up to 100%.

Related Link

[Global] Accelerating sustainability & circular economy (Japanese language only)