Dentsu, together with eight domestic Dentsu Group companies, has created “Everyone’s Communication Design Guide, (MinCom)” which aims to realize communication where “no one is left behind.” The guide has been publicly available since January 28, 2025.

In this series of articles, members of the MinCom secretariat share examples that contribute to diversity and inclusion in communication, while also exploring their social significance.

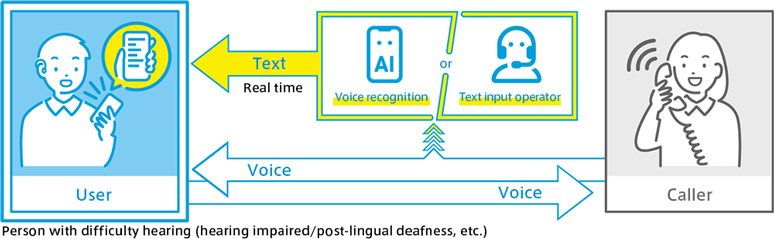

In the spotlight in this article is the captioned telephone service “Yometel,” a smartphone app that transcribes your caller’s voice and displays it as text. Yometel started as a service for people who have difficulty hearing their caller’s voice when speaking on the phone. So why was it expanded and developed into an app that converts caller’s voices to text? Delve into the background to this service and you discover the existence of approximately 14.3 million people (*1) who experience difficulty communicating by telephone due to hearing impairments or other reasons.

So what must we do to create a society that embraces the diverse “everyone,” where all people can enjoy the benefits of communication?

| *1 | According to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, there are approximately 14.3 million people with some degree of hearing loss nationwide (about 10% of the entire population). |

Telephone Relay Service as a vital public infrastructure for people’s daily lives

Nomura: From January 23, 2025 you launched “Yometel,” a phone service that enables the user to read their caller’s voice. Can I start by asking you to give a quick introduction to the Yometel service?

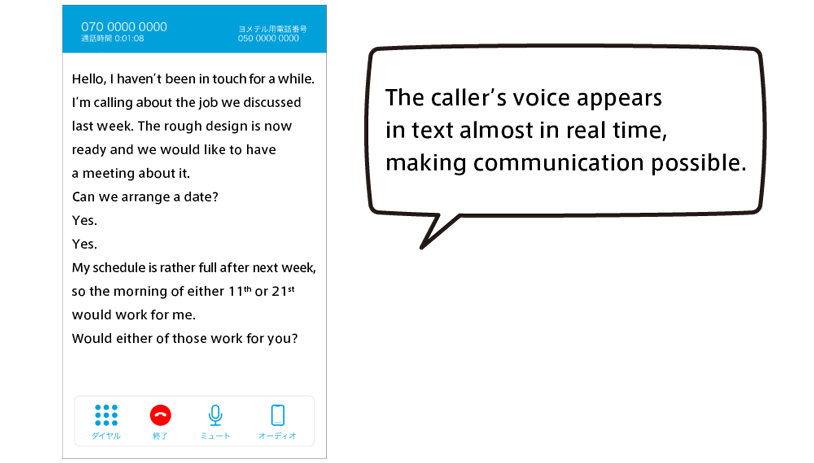

Uemura: Yometel is a smartphone-based app that converts a caller’s voice to text. This services is designed for people who may experience difficulty hearing their caller’s voice on the phone, such as the hearing impaired or those with post-lingual deafness. Another feature is that it can be used bidirectionally 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. By converting a caller’s voice to text, it has become one of the public infrastructures based on law that today facilitates smooth telephone-based communication.

Nomura: You mentioned that the service is provided based on law. Could you tell us about the social background that led to the development and launch of the Yometel service?

Koshiishi: Let me start by explaining a little about telephone relay services. The telephone is a fundamental communication tool that enables real-time communication among people who are in different places, and it plays a particularly important role in emergencies and disasters. However, due to the nature of telephones using voice communication, people with hearing or speech impairments find them difficult to use. This inability to make phone calls independently in emergencies was a major problem and one that was also potentially life-threatening.

The telephone relay service, which was already in operation overseas, was developed to solve these various challenges. This service allows people who struggle with the telephone to communicate through an interpreter operator, who conveys messages in sign language or text.

In Japan, The Nippon Foundation began providing this service as a model project in September 2013, realizing bidirectional communication by having interpreter-operators interpret sign language and text into voice for conversations between people with hearing or speech impairments and people who are able to hear.

Thereafter, in FY2020, just as The Nippon Foundation’s model project service was scheduled to end, discussions were held in the Telephone Relay Service Working Group of the Council for Realizing an Inclusive Society through Digital Utilization, with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications considering system development. Then, in June 2020, the “Act on Facilitation of the Use of Telephones for Persons with Hearing Impairments, etc.” was passed. The telephone relay service was then formulized (*2), and service provision as public infrastructure began in FY2021.

Nomura: I see. So the telephone relay service was formally established so that anyone could use it anytime, and established as public infrastructure.

| *2 | Based on the law, The Nippon Foundation Telecommunications Relay Service, which is designated by the Minister of Internal Affairs and Communications as the sole nationwide telephone relay service provider, provides services and conducts awareness activities. |

Everyone has their own unique challenges and needs. The starting point is to understand the diverse “everyone”

Nomura: So what issues led to the development of the Yometel app and the provision of the service?

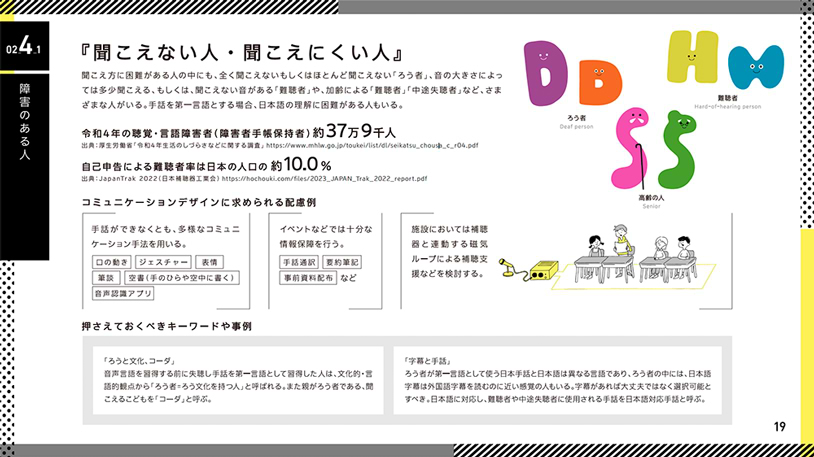

Nishikawa: The telephone relay service that we launched previously is a service where interpreter-operators interpret conversations between people with hearing or speech impairments and people who can hear, using sign language, text and voice. According to a survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, there are currently approximately 379,000 people with hearing and speech impairments (disability certificate holders) (*3) in Japan. Among these people, slightly fewer than 80,000 people are said to use sign language. This telephone relay service is a service that can be used by people who use sign language.

However, the self-reported hearing loss rate is said to be about 10% of Japan’s total population (*4).

| *3 | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “2022 Survey on Difficulties in Everyday Life, etc.” |

| *4 | Japan Hearing Instruments Manufacturers Association (JHIMA) survey “JapanTrack 2022.” |

Uemura: In the case of people who become deaf later in life, they were accustomed to using voice communication until they lost their hearing, so many people still want to use their own voice. However, they cannot hear or have difficulty hearing the other caller’s voice, making it challenging to use the telephone.

The telephone relay service is a service for making phone calls using sign language or text, so users are unable to communicate using their own voice. Therefore, there has long been an outstanding need for a service that enhances the other caller’s voice while using one’s own voice.

Nomura: Were such services already in operation overseas?

Uemura: There are similar needs overseas, and in the United States and elsewhere, there is what is known as a Captioned Telephone Service (CTS). Therefore, there was already demand in Japan for a service like CTS, which is what spurred on the development of Yometel.

Koshiishi: Until now, the telephone relay service could only be used by a limited number of people, but with the introduction of Yometel, options have now increased.

Nomura: The MinCom Guide also highlights that there are people with disabilities who have diverse needs. Yometel is precisely one of the services that responds to such diverse needs, isn’t it?

The MinCom Guide features data stating that “the self-reported hearing loss rate is about 10% of Japan’s total population.” This underscores the fact that there are more people than we might think who are struggling with hearing impairments or hearing loss.

Uemura: That’s exactly right. I hope that as many people as possible will realize the fact that the phrase “hearing impairment” isn’t just a single condition – it is much broader than that.

Perfect for people concerned about declining aural capabilities! Yometel helps to enhance quality of life

Nomura: What did you focus on when developing and operating the Yometel app?

Uemura: As Ms. Koshiishi mentioned earlier, the telephone is a fundamental tool for communication between people who are in different places. We fully reflected that principle into the Yometel app and developed it with a focus on a simple user experience, so as not to create a gap in usage compared to the telephone functions built into iPhone and Android operating systems.

Nishikawa: We conducted a pilot test last summer, seeking to realize ease of use, while also receiving input from many people involved. In particular, the speed at which the other caller’s voice is converted to text and the text’s readability, as well as functions like outgoing and incoming calls were aspects that were developed through discussions that incorporated the opinions of the people directly concerned.

In addition, the method for converting the other caller’s voice to text allows users to choose between AI (automatic speech recognition) and text input operators, making it possible to use AI when prioritizing speed and seeking a more realistic phone conversation, and text input operators when seeking higher accuracy.

Uemura: Although some people may not feel unduly inconvenienced in their daily lives, they may experience difficulty hearing the more mechanized sounds of a phone. Such people can use Yometel to check the text just for the parts they couldn’t hear very well.

Nomura: It is also to be hoped that people with age-related hearing loss, those with sudden hearing loss, and those concerned about declining hearing due to conditions such as Ménière’s disease—which is said to be more common among women—will make use of this service too. Although the service hasn’t been in operation for very long, how is the adoption rate doing?

Nishikawa: Judging from the people who have registered to use the service, current users are those who had been waiting eagerly for its roll-out and who signed up immediately to use it. However, as the data shows, approximately 10% of Japan’s population is said to have some kind of hearing impairment, so there is potential for one in ten people to become Yometel users. Looked at from this perspective there are still many potential users and the challenge for us it to ensure that information reaches such people.

We plan to continue our outreach and awareness-raising efforts going forward, including reviewing the registration method, and holding explanation sessions and seminars.

Aiming for a society where everyone has equal access to information. What is the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications doing to promote information accessibility?

Nomura: The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications oversees administrative functions related to people’s living infrastructure, such as local governance and social infrastructure. I believe that it is also in charge of information and communications infrastructure development. Given today’s world in which the internet is transforming society, what do you feel are the key priorities and challenges that require the ministry’s attention?

Koshiishi: Today anyone can easily get online using a variety of terminals, from smartphones to PCs, tablets and other devices. Given that so much information is readily available, what is vitally important is to ensure information accessibility. This means that everyone, regardless of age or disability, can easily find and utilize the information they require.

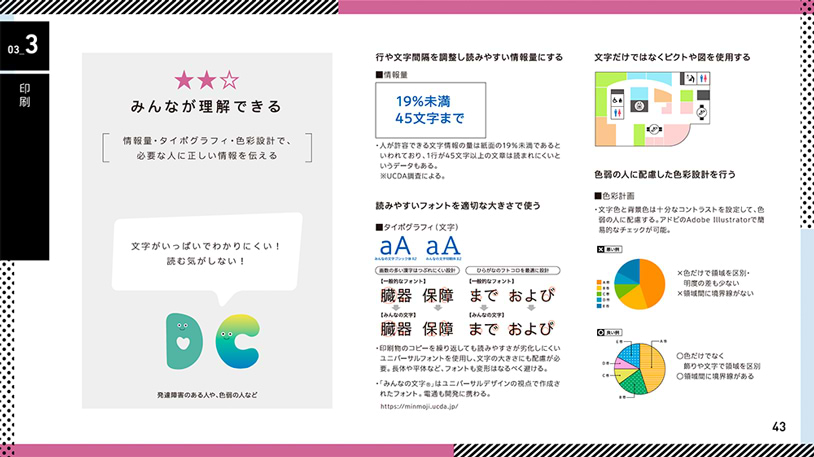

To give some straightforward examples, one needs to consider whether an easy-to-read font such as a universal design (UD) font is being used, whether sentences are kept from becoming overly long and difficult to follow, whether difficult kanji are accompanied by furigana, and whether colors are chosen with consideration for people with color vision impairments or older adults. There are many such points that deserve attention. However, my feeling is that many of these can be resolved simply with just a little consideration from the information provider.

Nomura: The MinCom Guide also introduces key considerations and useful examples, based on the assumption that there are recipients with diverse needs, such as gender, age, and disability.

■ Print media

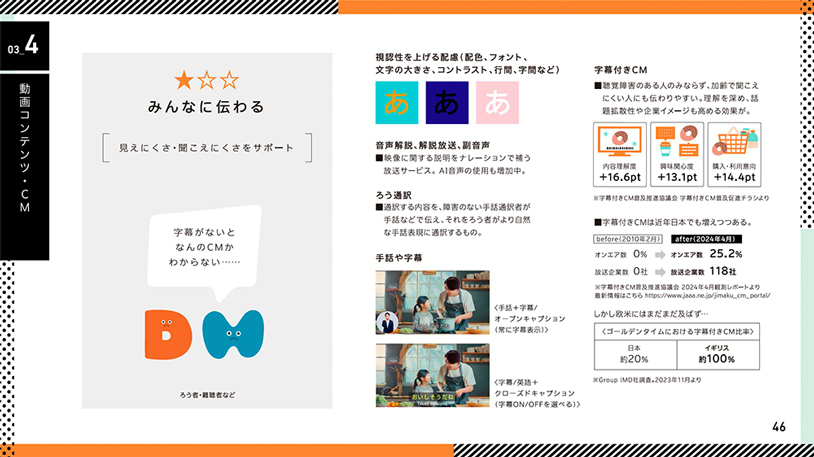

■ Video content / commercials

Koshiishi: Having guides like this to set things out makes everything easier to understand.

In terms of website accessibility, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications has also published “Guidelines on Operation and Management of Public Website for Everyone.” National and local government organizations and other public institutions disseminate a lot of important information for citizens on their websites and other platforms. That is why we present standards and procedures on web accessibility and call for improved web accessibility so that anyone, including the elderly and people with disabilities, can easily get online.

Nomura: Now that various information can be acquired on the internet, improving web accessibility is an important issue that should be recognized not only by public institutions but also by many companies.

Koshiishi: Exactly. It is also necessary to bear in mind that among information recipients there are people with various characteristics, such as those with visual impairments, those with dyslexia (a learning disability involving difficulties with reading and writing), and people whose native language is not Japanese.

I hope that people will first think about the kind of people they want to convey information to, and then use the “Guidelines on Operation and Management of Public Website for Everyone” as a reference for designing things like font size, video transition methods, and audio timing.

I feel that as more companies and organizations engage in improving web accessibility, so in turn will everyone be able to acquire information without inconvenience, which will eventually lead to realizing communication where no one is left behind.

Nomura: Also, while the world has undoubtedly become more convenient, various internet-related problems have emerged, such as false and misleading information, illegal part-time job solicitation, and online casinos. Could you tell us about any countermeasures the ministry is working on to combat such issues?

Koshiishi: Starting in January 2025, the ICT Accessibility Office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications has begun an initiative called DIGITAL POSITIVE ACTION. Each citizen needs to improve their information literacy so as not to be deceived by or spread fake information.

It is precisely because we all live in the internet era that the first step towards a truly inclusive society is for everyone to deepen their understanding about information accessibility and literacy and put what they know into practice.

Nomura: Hearing what everyone has said here today has reaffirmed for me the vital necessity to imagine the characteristics and needs of the people who are our counterparts in communication. . I hope that we can put into practice what is possible to do, from consideration for information accessibility to improvement of information literacy. Thank you very much for your valuable insights and opinions today.

What is Everyone’s Communication Design?

A way of thinking that aims to realize ideal communication for everyone where “no one is left behind,” based on the premise that communication targets include recipients with diverse characteristics and needs such as age, presence or absence of disability, gender, and nationality. The “MinCom Guide” highlights the diverse “everyone,” examining the many communication media that are available for use between senders and receivers, and introducing key considerations along with useful examples.